‘Books’ Category Archives

Aug

Read George Saunders’ Titular Story from His Short Story Collection “Tenth of December”

by Lefort in Books

We are coming off a bender. A word and image bender. A word bender of brilliance, hilarity, fright, disquietude, and uplift. All in one short story collection. We’ve just feasted on George Saunders’ short story collection, Tenth of December, and like many before us (read, for example, The New Yorker’s article George Saunders Has Written the Best Book You’ll Read This Year HERE), we heartily recommend these awe-inspiring writings to you. Tenth of December may now stand as our favorite of all-time in the genre. If you like short stories, or even if you don’t (true confession: not our favorite genre), this book will knock you back and cause you to take stock. These stories are not for the faint of heart (since: life), but your courage and fortitude will be gravely rewarded (if you will). The gravitas is, however, leavened throughout with satire and hilarious wordplay.

For a sample, you can go over to The New Yorker HERE and read the title story (which is simply one of the best short stories we’ve ever read). And if you like it, there’s much more where that came from in Tenth of December. Highly recommended. Excuse us while we head off to purchase every other George Saunders book that’s been published.

Aug

Jess Walter’s “Beautiful Ruins”–a Beautiful Read

by Lefort in Books

It’s been a long time since we took time to tout a tome. It’s not like we’ve stopped reading, but there just simply aren’t enough posts in a day (reasonable minds may differ). Simply put, Jess Walter’s most recent book, Beautiful Ruins, is the most enjoyable read we’ve had in quite some time. If you need a great novel to finish out the summer’s days, this is it.

Jess Walter is an award-winning storyteller (Citizen Vance, The Zero) who is facile in all genres, including non-fiction. But with Beautiful Ruins, he’s outdone himself. Walter introduces us to a dozen characters whose lives are, knowingly and unknowingly, intertwined over a span of 70 years, ranging from a dying actress and Richard Burton on a movie set and elsewhere in Italy in 1962, to an Italian innkeeper, to a Hollywood producer, to the producer’s idealistic assistant, to a heartbroken World War II veteran. Together with their spouses, lovers, progeny and friends, Walter weaves a tale of success, failure, heartbreak, resignation and resolve. You know: life. In the course of doing so, Walter uses every literary trick in the proverbial book to capture the human condition, though all in service of the story and never merely for show. Early on, the chapters alternate between the various eras to great effect. Eventually Walter uses virtually all literary tropes available to tell the tale: poetry, short story, movie pitch-piece, memoir, play, screenplay…they’re all there. And all are used in service of the captivating storylines. If it sounds at all mechanical, it is not. The highly entertaining pages fly by. Walter is at his best capturing conversation and using pathos and bathos (some of Burton’s lines had us laughing aloud) to illumine the characters and their interlaced lives. And he does it so well and so deftly that you won’t realize how entertained you’ve been in the process.

We will be shocked if, as a result of this must-read novel, Walter doesn’t take home many of the literary prizes available for 2012.

Oct

Keith Richards’ “Life”–Our Favorite Excerpts

by Lefort in Books, Music

Yeah, we’re the late show on this. But a couple weeks ago we finally finished Keith Richards’ immensely entertaining and illuminating memoir, “Life.”

The following were amongst our favorite passages (emphasis added):

Richards on touring:

“The grind is the traveling, the hotel food, whatever. It’s a hard drill sometimes. But once I the stage, all of that miraculously goes away. Thee grind is never the stage performance. I can play the same song again and again, year after year. When Jumping Jack Flash comes up again it’s never a repetition, always a variation. Always. I would never play a song again once I thought it was dead. We couldn’t just churn it out. The real release is getting on stage. Once we’re up there doing it, it’s sheer fun and joy. Some long-distance stamina, of course, is needed. And the only way I can sustain the impetus over the long course we do is by feeding off the energy that we get back from the audience. That’s my fuel. All I’ve got is this burning energy, especially when I’ve got a guitar in my hands. I get an incredible raging glee when they get out of their seats. Yeah, come one, let it go. Give me some energy and I’ll give you back double. It’s almost like some enormous dynamo or generator. It’s indescribable. I start to rely on it; I use their energy to keep myself going. If the place was empty, I wouldn’t be able to do it. Mick does about ten miles. I do about five miles with a guitar around my neck, every show. We couldn’t do that without their energy, we just wouldn’t even dream of it. And they make us want to give our best. We’ll go for things that we don’t have to. It happens every night we go on. One minute we’re just hanging with the guys and oh, what’s the first song?…, and suddenly we’re up there. It’s not that it’s a surprise, because that’s the whole reason to be there. But my whole physical being goes up a couple of notches. “Ladies and gentlemen, the Rolling Stones.” I’ve heard that for forty-odd years, but the minute I’m out there and hit that first note, whatever it is, it’s like was driving a Datsun and suddenly it’s a Ferrari. At that first chord I play, I can hear the way Charlie’s going to hit into it and the way Darryl’s going to play into that. It’s like sitting on top of a rocket.”

Richards on the negative effects of “improved” recording technology:

“Very soon after Exile, so much technology came in that even the smartest engineer in the world didn’t know what was really going on. How come I could get a drum sound back in Denmark Street with one microphone, and now with fifteen microphones I get a drum sound that’s like someone shitting on a tin roof? Everybody got carried away with technology and slowly they’re swimming back. In classical music, they’re rerecording everything they rerecorded digitally in the ’80s and ’90s because it just doesn’t come up to scratch. I always felt that I was actually fighting technology, that it was no help at all. And that’s why it would take so long to do things. [Producer] Fraboni has been though all of that, that notion that if you didn’t have fifteen microphones on a drum kit, you didn’t know what you were doing. Then the bass player would be battened off, so they were all in their little pigeonholes and cubicles. And you’re playing this enormous room and not using any of it. This idea of separation is the total antithesis of rock and roll, which is a bunch of guys in a room making a sound and just capturing it. It’s the sound they make together, not separated. This mythical bullshit about stereo and high tech and Dolby, it’s just totally against the whole grain of what music should be.

Nobody had the balls to dismantle it. And I started to think, what was it that turned me on to doing this? It was these guys that made records in one room with three microphones. They weren’t recording every little snitch of the drums or bass. They were recording the room. You can’t get these indefinable things by stripping it apart. The enthusiasm, the spirit, the soul, whatever you want to call it, where’s the microphone for that? The records could have been a lot better in the ’80s if we’d cottoned on to that earlier and not been led by the nose of technology.”

Richards on Tom Waits:

“Tom Waits was an early collaborator…He’s a one-off lovely guy and one the most original writers.”

Tom Waits on the first time he met and played with Richards:

“We were doing Rain Dogs…. He played on three songs on that record: “Union Square,” we sang on “Blind Love” together, and on “Big Black Mariah” he played a great rhythm part. It really lifted the record up for me. I didn’t care how it sold at all. As far as I was concerned it had already sold.”

Tom Waits on the Wingless Angels recording (recorded in part outside live in Jamaica):

“One of my favorite things that he did is Wingless Angels. That completely slayed me. Because the first thing you hear is the crickets, and you realize you’re outside. And his contribution to capturing the sounds on that record just feels a lot like Keith. Maybe more like Keith than I had contact with when we got together. He’s like a common laborer in a lot of ways. He’s like a swabby. Like a sailor. I found some things they say about music that seemed to apply to Keith. You know, in the old days they said that the sound of the guitar could cure gout and epilepsy, sciatica and migraines. I think that nowadays there seems to be a deficit of wonder. And Keith seems to still wonder about this stuff. He will stop and hold his guitar up and just stare at it for a while. Just be rather mystified by it. Like all the great things in the world, women and religion and the sky … you wonder about it, and you don’t stop wondering about it.“

Aug

Attention All You Murakami-Loving Cats

by Lefort in Books

The New Yorker has published (at the link way below) the first extended excerpt from Haruki Murakami’s new, 1000-page novel, 1Q84, which will be released on October 25th. Not surprisingly, it appears that felines will be a quintessential part of the equation.

The novel was originally published in Japan as a trilogy in 2009 and 2010. Knopf will publish the novel in the United States in a single volume on October 25, 2011. The title is a play on the Japanese pronunciation of the year 1984, a reference to George Orwell’s seminal novel.

According to various sources:

“The events of the story take place in fictionalized 1984, with the first volume set between April and June, the second between July and September, and the third between October and December. The narrative is composed of two storylines that alternate by chapter. The book opens with on character’s (Aomame’s) perspective as she catches a taxi in Tokyo on her way to a work assignment, noticing that Janáček’s Sinfonietta [Lefort: Any novel that references the great Czech composer, Janacek, in the first chapter is bound to be great.] is playing on the radio. When the taxi gets stuck in a traffic jam on the expressway, the driver suggests that she get out of the car and climb down an emergency escape in order to make her important meeting. Aomame makes her way to a hotel in Shibuya, where she poses as a hotel attendant in order to assassinate a hotel guest. She performs the murder with a tool that leaves almost no trace on its victim, leading investigators to conclude that he died a natural death.

As the story unfolds, Aomame has several bizarre experiences, including a string of memories that do not line up with the archives of major newspapers. One of them concerns a group of extremists who are engaged in a standoff with police in the mountains of Yamanashi Prefecture. Upon reading these articles, she concludes that she must be living in an alternate reality, and suspects that she entered it about the time she heard the Sinfonietta on the radio.”

And that’s just the first chapter and segment of the novel. In typical Murakami fashion, the novel will undoubtedly get only more fantastical and fantastic thereafter.

The novel entails the usual Murakim matters: murder, history, cult religion, violence, family ties, cats and love. The Japan Times reviewer said that the novel “may become a mandatory read for anyone trying to get to grips with contemporary Japanese culture“, calling 1Q84 Haruki Murakami’s “magnum opus.”

We’ve loved Murakami’s other-worldly novels (especially The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and Kafka on the Beach) and can’t wait to delve into 1Q84. If you haven’t read any Murakami, we encourage you to do so. Just be prepared for lots of magic and some realism, and all as set in (mostly) contemporary Japan.

Check out the New Yorker excerpt HERE. And while you’re at it, you might as well have the Sinfonietta playing in the background per below.

Aug

Summer’s Books

by Lefort in Books

So far it’s been a good summer for reading novels. Insomnia can contribute to the quantity of reading, if not the quantity of retention. If you need a good read, you may be able to find one to suit you below. Presented in our order of preference, though the last one is probably the closest to a “Summer Read” of the lot.

A Visit From the Goon Squad by Jessica Egan (2010 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction–and which we unprecedentedly read twice–in a row)

Those Pulitzer folks rarely get it wrong, and Egan’s book is no exception. This book won this year’s Pulitzer for fiction, and it is a Lefort favorite in part because it streams music and the music industry within its lines. You can feel the fab Mabuhay and the Dead Kennedys along the way, and the socially engineered performance at the end. Egan uses the music industry in this novel as a case study for this world’s seismic shift from the analog to the digital age (near the end of the book, 75 pages are allotted to a child’s powerfully poetic Powerpoint presentation). But the book is also a carefully crafted character study. Egan flashes forwards and back in time to develop those characters and illumine the digital evolution’s effects on our society, and at times it can feel that the novel is more a collection of short stories barely tethered together by some through-lines. The net effect can be intermittently confusing and jarring, but in the end one realizes the magic that Egan has conjured. The themes are not for the faint of heart (sex and drugs and rock n’ roll, etc.), but the writing and affect are profound.

Some lines from the book we particularly enjoyed:

About a therapist: “[H]e was old school inscrutable, to the point that Sasha couldn’t tell if he was gay or straight, if he’d written famous books, or if (as she sometimes suspected) he was one of those escaped cons who impersonate surgeons and wind up leaving their operating tools inside people’s skulls.”

A record producer reminiscing about his mentor: “[Bennie] remembered his mentor, Lou Kline, telling him in the nineties that rock and roll had peaked at Monterey Pop They’d been in Lou’s house in LA with its waterfalls, the pretty girls Lou’s always had, his car collection out front, and Bennie had looked into his idol’s face and thought, You’re finished. Nostalgia was the end–everyone knew that.”

The foregoing expresses what drives us to keep reaching out for new music. Of course we can’t ignore the canonical music past, but we also shouldn’t settle in on the familiar. Instead we need to be challenged, even shocked, by new music, and continue to grow. Or else you’ll be finished. Who was it said: “He not busy being born is busy dying”?

And from our favorite chapter in the book, a journalistic “report” by reporter Jules Jones about his interview with young starlet, Kitty Jackson, which does not end well: “And since the ten minutes of badinage I proceed to exchange with Kitty are simply not worth relating, I’ll mention instead (in the footnote-ish fashion [Lefort: the footnotes are fantastically written] that injects a whiff of cracked leather bindings into pop-cultural observation) that when you’re a young movie star with blondish hair and a highly recognizable face from that recent movie whose grosses can only be explained by the conjecture that every person in America saw it twice, people treat you in a manner that is somewhat different…from the way they treat, say, a balding, stoop-shouldered, slightly eczematous guy approaching middle age.”

The publisher has this to say about the book:

“Jennifer Egan’s spellbinding interlocking narratives circle the lives of Bennie Salazar, an aging former punk rocker and record executive, and Sasha, the passionate, troubled young woman he employs. Although Bennie and Sasha never discover each other’s pasts, the reader does, in intimate detail, along with the secret lives of a host of other characters whose paths intersect with theirs, over many years, in locales as varied as New York, San Francisco, Naples, and Africa.

We first meet Sasha in her mid-thirties, on her therapist’s couch in New York City, confronting her long-standing compulsion to steal. Later, we learn the genesis of her turmoil when we see her as the child of a violent marriage, then as a runaway living in Naples, then as a college student trying to avert the suicidal impulses of her best friend. We plunge into the hidden yearnings and disappointments of her uncle, an art historian stuck in a dead marriage, who travels to Naples to extract Sasha from the city’s demimonde and experiences an epiphany of his own while staring at a sculpture of Orpheus and Eurydice in the Museo Nazionale. We meet Bennie Salazar at the melancholy nadir of his adult life — divorced, struggling to connect with his nine-year-old son, listening to a washed-up band in the basement of a suburban house — and then revisit him in 1979, at the height of his youth, shy and tender, reveling in San Francisco’s punk scene as he discovers his ardor for rock and roll and his gift for spotting talent. We learn what became of his high school gang — who thrived and who faltered — and we encounter Lou Kline, Bennie’s catastrophically careless mentor, along with the lovers and children left behind in the wake of Lou’s far-flung sexual conquests and meteoric rise and fall.

A Visit from the Goon Squad is a book about the interplay of time and music, about survival, about the stirrings and transformations set inexorably in motion by even the most passing conjunction of our fates. In a breathtaking array of styles and tones ranging from tragedy to satire to PowerPoint, Egan captures the undertow of self-destruction that we all must either master or succumb to; the basic human hunger for redemption; and the universal tendency to reach for both — and escape the merciless progress of time — in the transporting realms of art and music.”

“Next” by James Hynes (Believer Magazine’s Book of 2010)

Believer Mag knows what it’s talking about. “Next” is both a serious and a comedic look at middle-age, relationships and the state of the modern world. Who cannot read themselves in some pages or lines of this book? Hynes mesmerizes throughout, but nothing could prepare us for the implausible, but perfect, ending. We loved this book, which is thus described on the author’s website:

“Descending on a plane into Austin, Texas, Kevin Quinn is worried about his stifling job, the younger girlfriend he’s lucky to have but can’t commit to, his rapidly encroaching late middle age, and the terrorist attacks in Europe that rocked the world just days ago. But as the tarmac looms closer, he’s really thinking about only one thing: the beautiful young woman in the seat next to him. Though he should be focused on the job interview that’s brought him to Texas in the first place, Kevin can’t quite let his luminous seatmate go. He impulsively takes off after her through the city streets in a quixotic and nostalgic journey that evokes scenes from his past: his dodgy love life, recollected in hilariously mortifying detail; the tragicomedy of his youthful idealism; the dysfunctional family he has only ever wanted to escape. It’s a day both common in its anxieties and singular for the fresh possibilities the girl and the interview represent. Then, on the fifty-second floor of an Austin office tower, as he takes the first steps toward what he hopes might be a late-in-life second chance, Kevin is suddenly confronted with a shocking reality about himself, and the age we live in. Perhaps, in the nick of time, he will understand just what happens next.”

“The Great Man” by Kate Christensen (winner of the 2007 Pen/Faulkner Award)

Christensen has quickly become one of our favorite authors. Her character sketches and stories of middle/old age and intertwined relationships are perfectly rendered here, along with a good glimpse into the lives and foibles of painters. Who knew that a novel consisting mostly of septa- and octo-generian characters could be such a page-turner?

Christensen’s website describes the book thus:

“Oscar Feldman, the renowned figurative painter, has passed away. As his obituary notes, Oscar is survived by his wife, Abigail, their son, Ethan, and his sister, the well-known abstract painter Maxine Feldman. What the obituary does not note, however, is that Oscar is also survived by his longtime mistress, Teddy St. Cloud, and their daughters. As two biographers interview the women in an attempt to set the record straight, the open secret of his affair reaches a boiling point and a devastating skeleton threatens to come to light.”

Sunset Park by Paul Auster

Paul Auster has recently experienced his most prolific period as a novelist, with “Sunset Park” being his seventh book in eight years (we have read and enjoyed “Invisible,” “The Brooklyn Follies” and “The Book of Illusions” in particular). Sunset Park is the latest and best of this prolific “late period” for Auster.

The book’s publisher puts it this way:

“Sunset Park follows the hopes and fears of a cast of unforgettable characters brought together by the mysterious Miles Heller during the dark months of the 2008 economic collapse. An enigmatic young man employed as a trash-out worker in southern Florida obsessively photographing thousands of abandoned objects left behind by the evicted families. A group of young people squatting in an apartment in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. The Hospital for Broken Things, which specializes in repairing the artifacts of a vanished world. William Wyler’s 1946 classic The Best Years of Our Lives. A celebrated actress preparing to return to Broadway. An independent publisher desperately trying to save his business and his marriage. These are just some of the elements Auster magically weaves together in this immensely moving novel about contemporary America and its ghosts.”

An Object of Beauty by Steve Martin

Comedian, actor, musician, playwright, painter, art-collector and, it turns out, novelist, Steve Martin has written a surprisingly good novel depicting the artists, dealers, and other players in the New York City art world. This is a serious (and intermittently hilarious) novel that informs on the art scenesters and surprises on many fronts (including that Martin can even write romance scenes with aplomb).

Martin’s website describes the book this way:

“A captivating presence who naturally draws in everyone around her, Lacey Yeager appears on the New York art scene as a clever and funny young intern at Sotheby’s. With her charm, ambition, and questionable and sometimes illegal tactics, she climbs the cultural ladder, step by step, and moves from cataloging paintings to success in the labyrinthine and mysterious art world. Her knowledge of art and art collectors quickly grows, and the list of men she enchants and inevitably destroys grows right alongside it. Her rise to the highest tiers of the city’s social life parallel the soaring heights—and, at times, the dark lows—of the art world and the country from the early 1990s through today.”

The Astral by Kate Christensen

Christensen. Again. Though not quite as perfectly realized as The Great Man, by novel’s end Christensen has once again brought her characters to full life and painted well their sorrows, joys and regrets. It ain’t always pretty, but that’s life.

Her website says this of the novel:

“The Astral is a huge, rose-colored old pile of an apartment building in the gentrifying neighborhood of Greenpoint, Brooklyn. For decades it has been the happy home (or so he thought) of the poet Harry Quirk and his wife, Luz, a nurse; and their two children, Karina, now a fervant freegan, and Hector, who has fallen into the clutches of a cultish [Lefort: faux-]Christian community. But when Luz finds (and destroys) some poems of Harry’s that ignite her long-simmering suspicions of infidelity, she summarily kicks him out. Suddenly he must reckon with the consequence of his literary, marital, financial, and parental failures and find his way forward.”

Heads You Lose by Lisa Lutz + David Hayward

For those in need of an intermittently hilarious whodunit that practically turns its own pages, we recommend “Heads You Lose.”

Penguin blurbs this about the book:

“From New York Times–bestselling author Lisa Lutz and David Hayward comes a hilarious and original tag-team novel that reads like Weeds meets Adaptation. [Lefort: Lutz wrote the first chapter and emailed it to Hayward without outline or storyline pre-conceptions; the authors then take turns writing chapters, not knowing the twists and turns to the story each will fashion along the way.]

Meet Paul and Lacey Hansen: orphaned, pot-growing, twentysomething siblings eking out a living in rural Northern California. When a headless corpse appears on their property, they can’t exactly dial 911, so they move the body and wait for the police to find it. Instead, the corpse reappears, a few days riper … and an amateur sleuth is born. Make that two.

But that’s only half of the story. When collaborators Lutz and Hayward—former romantic partners—start to disagree about how the story should unfold, the body count rises, victims and suspects alike develop surprising characteristics (meet Brandy Chester, the stripper with the Mensa IQ), and sibling rivalry reaches homicidal intensity. Will the authors solve the mystery without killing each other first?”

Mar

Read a Book or Two

by Lefort in Books

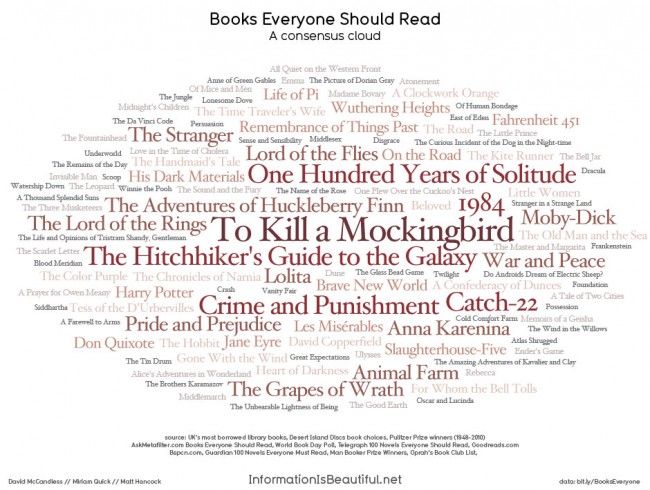

We at Lefort have resolved to read at least two books per month. So far so good, but the year is young. The reading of books and novels seems to occur less frequently each year by the general populous, though we know many of you are the exceptions to that trend. If you need any book ideas, below is a “Consensus Cloud” graphic depicting the most frequently cited books from various “best of” sources (the larger the title in the graphic, the more frequently cited). You can read more about the graphic and its creation in the Guardian here.

Feb

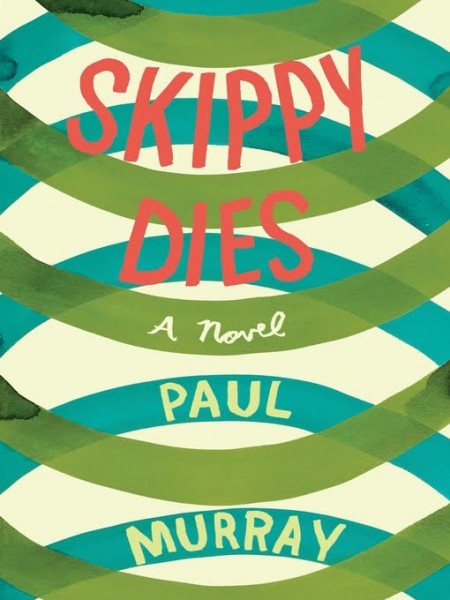

Skippy Dies by Paul Murray

by Lefort in Books, Music

We just finished the thoroughly engaging novel, Skippy Dies, by Irish author, Paul Murray. Skippy Dies was nominated for the 2010 Booker Prize and a National Book Critics Circle award in Fiction, and was prevalent on many “Top Books of 2010” lists. And for you cinemistas, we understand that the book is to be adapted for the big screen by none other than Neil Jordan.

No Spoilage Alert: We won’t be giving anything away by telling you that Skippy, the main character in this fine novel, in fact perishes early in this book. By page 5 in fact. After this skeletal opening segment, Murray goes back in time to flesh out the body of the story and provide the circumstances that lead to the passing of the innocent, sweet Skippy—a 14-year-old student at a venerable Catholic boys’ prep school in Dublin. In time we are introduced to Skippy’s adolescent prep school chums and nemeses, his young and old teachers, his girlpop-loving love-interest, the schools’ callous administration (there’s a shocker), and the neurotic parents of these teenagers. We also learn of the unexpectedly viral consequences of Skippy’s death, get a feel for contemporary Irish life and history, and learn a great deal about the theoretical intertwining of science (quantum physics, string theory, etc.) and metaphysics. Murray has delivered a very ambitious and dense coming-of-age novel that is at times hilarious and at other times harrowing and heartbreaking.

In short, it’s life writ large.

You can read a well-done review by Dan Kois in the New York Times here.

Paul Murray has said this to say about the book elsewhere:

“I started writing Skippy Dies in 2002. The book is set in a school in South Dublin in Ireland. It revolves around a group of fourteen-year-old boys, Skippy being the hero, or the antihero, who falls for Lori, a (dangerously) beautiful girl from the convent school next door. In the opening scene, he dies during a doughnut-eating race with his roommate, Ruprecht, and writes Lori’s name on the floor in strawberry syrup; the book then tracks back to discover how his death came about.

Writing about teenagers was liberating in many ways, because their emotional lives are so dramatic and so unconcealed. They could plausibly say or do almost anything; you could really push things to the limit. I worked hard to capture the intensity of feeling you experience as a teenager – the sense of connection you can feel for your friends, to the point of turning into each other, the sense of adoration you can have for a girl or a boy you hardly know, the loneliness and confusion and despair you can feel for no reason at all.”

One of the most touching passages of the novel (excerpted below) involves music (another shocker). Four of Skippy’s friends are called upon to play as a quartet in the prep school’s 140th anniversary celebration. These friends decide to use their playing of Pachelbel’s Canon in D in homage to Skippy and for purposes greater than the school’s anniversary.

Excerpt from Skippy Dies:

“And the music, when it begins, sounds so beautiful. Pachelbel’s familiar melody, worn threadbare by endless TV commercials for cars, life assurance, luxury soap, by street-performers in black-tie, mugging for tourists in high summer, by any number of attempts to invoke the Old-World Elegance, accompanied by haughty waiters bearing trayfuls of tiny cubes of cheese – tonight it seems to its audience entirely new, to the point of an almost painful fragility. What it is that makes it so imploring and so sweet, so disconcertingly (for the older members of the audience who have come tonight expecting merely to be pleasantly bored and now find themselves with lumps in their throats) personal? Something to do with the horn that large boy [Lefort–Skippy’s roommate and friend, Ruprecht] in the silver suit is playing, perhaps, a new-fangled instrument that looks like it must have been run over by a truck, but produces a sound that’s like nothing you’ve ever heard – a hoarse, forlorn sound that just makes you want to …

And then the voice comes in, and you can actually see a shiver run through the decorous crowd. Because there is no singer on the stage, and given Pachelbel’s Canon does not have a vocal part, listeners could be forgiven for mistaking it for a ghost’s, some spirit of the hall roused by the music’s beauty and unable to resist joining in, especially as the voice – a girl’s – has an irresistibly haunting quality, spare, spectral, carved down to its bare bones… But then one by one the audience members spot beneath the mike stand over to the right, ah, an ordinary mobile phone. But who is she? And what’s she singing? [Lefort–it’s in fact melancholy Lori, the love of Skippy’s life, singing a song by Bethani (a fictional singer we surmise representative of Britney Spears) from her room.]

You fizz me up like Diet Pepsi

You make me shake like epilepsy

You held my had all summer long

But summer’s over and you’re gone

Holy smokes – it’s Bethani! A new murmur of excitement, as younger spectators crane their necks to hiss in the ears of parents, aunts, uncles – it’s ‘3Wishes’, the song she wrote after she broke up with Nick from Four to the Floor, when there were all those pictures of her at her mum’s wearing skanky clothes and actually looking quite fat – some people said that was all just part of the publicity, but how could you think that if you listened to the words?

I miss the bus and the walk’s so long

I got split ends and my homework’s wrong

There’s a hole in my sneaker and gum on my seat

And the world don’t turn and my heart don’t beat

– which the girl who’s singing now fills with such longing, such loneliness, only amplified by the crackling of the phone, that even parents who viewed Bethani with suspicion or disapproval (often coloured, in the case of the dads, by a shameful fascination) find themselves swept up by its sentiments – sentiments that, separated from their r’n’b arrangement and grafted onto this melancholy spiraling music three hundred years old, reveal themselves as both heart-rending and also somehow comforting – because their sadness is a sadness everyone can recognize, a sadness that is binding and homelike.

And the sun don’t shine and the rain don’t rain

And the dogs don’t bark and the lights don’t change

And the night don’t fall and the birds don’t sing

And your door don’t open and my phone don’t ring

So that as the chorus comes around once more, you can hear young voices emerge from the darkness, singing along:

I wish you were beside me just so I could let you know

I wish you were beside me I would never let you go

If I had three wishes I would give away two,

Cos I only need one, cos I only want you

– so that for these few moments it actually seems that Ruprecht could be right, that everything, or at least the small corner of everything that is the Seabrook Sports Hall, is resonating to the same chord, the same feeling, the one that over a lifetime you learn a million ways to camouflage but never quite to banish – the feeling of living in a world of apartness, of distances you cannot overcome; it’s almost as if the strange out-of-nowhere voice is the universe itself, some hidden aspect that rises momentarily over the motorway-roar of space and time to console you, to remind you that although you can’t overcome the distances, you can still sing the song – out into the darkness, over the separating voids, towards a fleeting moment of harmony…”

In this passage, Murray has managed to perfectly capture and evince the transcendental magic of music and its potential for harmonizing effects on young and old alike (and together). And Pachelbel, coupled with a Britney-like voiceover? It’s the ultimate emotional mashup. Heck, we just might have to go back and listen closer to some Britney. Well played, Mr. Murray. Well played.

Nov

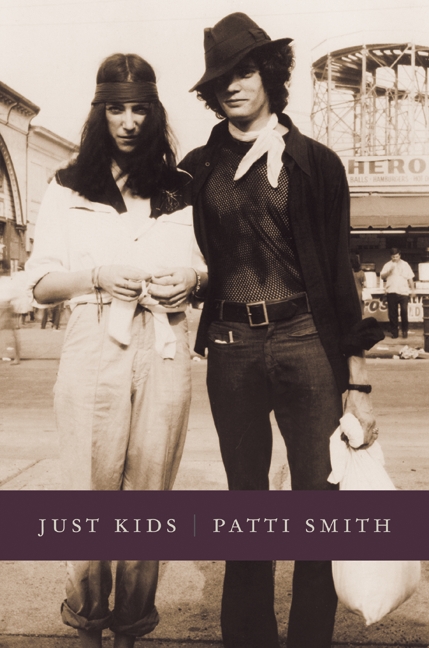

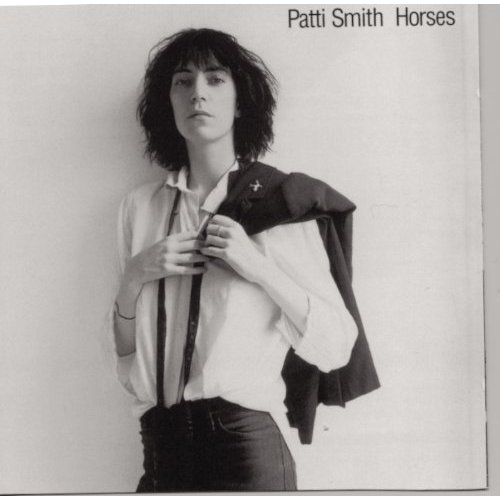

Patti Smith–Seminal Punker and National Book Award Winner

by Lefort in Books, Music

Seminal rocker, poet and artist, Patti Smith, recently received the National Book Award in Non-Fiction for “Just Kids,” her memoir of her close relationship with artist Robert Mapplethorpe and her rise in the New York City arts scene in the 70s.

A Rock and Roll Hall of Famer, Smith was one of the early progenitors of the New York City punk movement in the 70s, and “Just Kids” tracks her life from a bookish teenager in Pennsylvania to New York City in the early 70s where she befriended poet/gadabout Allen Ginsberg, dated playwright/actor Sam Shepard, and became an integral part of Andy Warhol’s scene. With respect to her music, “Just Kids” rightly focuses on her foundational album, “Horses,” which came out in 1975 and kick-started the NYC punk scene that begat The Ramones, Richard Hell, Television, and eventually the Talking Heads. “Just Kids” primary focus, however, is on Smith’s relationship with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe (his photo became the cover of “Horses” shown below). They were friends for years and lived and worked together as struggling/starving artists, and developed a mutual love for each other. It’s a fascinating and highly recommended read.

We fell in love with Patti and “Horses” from the start. Her cover of Gloria demanded your attention, but then rewarded with Birdland, Redondo Beach and a host of great songs. The first time we ever saw her perform was on Saturday Night Live on April 17, 1976. She was riveting and revelatory. A national audience that had been used to Elton John, KC and the Sunshine Band, and Steve Miller was asked to check out an androgynous, atonal beat poet doll-up a rousing version of Gloria (see way below) with lines about boys loving parking meters (that’s gotta hurt) and her lack of faith in Jesus.

Our favorite Patti Smith song is Redondo Beach. We have no idea the connection to the LA beach town, but the light-sounding, reggae-fied music contrasts with the dark lyrics regarding a lovers’ quarrel that leads to death. Smith asks over and over, “Are you gone-gone?” seemingly unable to accept the passing. It’s a melodic, but harrowing ride. High art. Check it out.

Patti Smith–Redondo Beach

[audio:https://www.thelefortreport.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/02-Redondo-Beach.mp3|titles=02 Redondo Beach]Aug

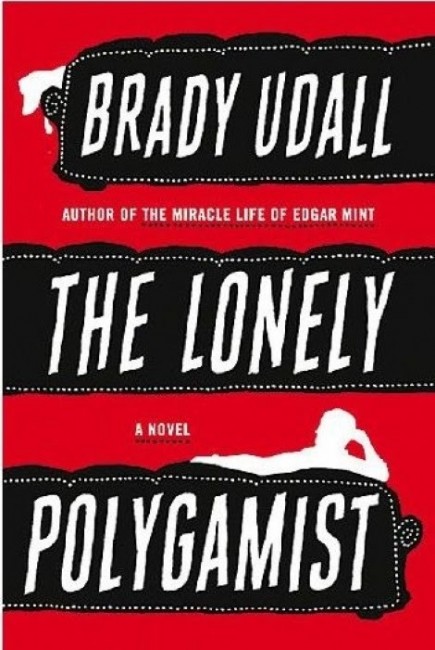

The Lonely Polygamist by Brady Udall

by Lefort in Books

We just finished The Lonely Polygamist by Brady Udall. In Udall’s latest book we find Golden Richards, polygamist husband to four wives and father to a scant twenty-eight children. We were not surprised, then, to read that Golden is in the throes of a major midlife crisis. His construction business is falling down all around him (though the book is not set in current times, but a couple of decades ago), and his family and wives are extremely demanding and needy, and are embroiled in various internecine battles (there’s a shocker). Add to this milieu Golden’s grand canyons of grief for the loss of two beloved children and you’ve got the recipe for an alternately elegiac and surprisingly humorous novel that provides a unique vantage into the Mormon fundamentalist life (we don’t get HBO, so did not catch the Big Love series).

We enjoyed Udall’s ability to humorously depict the polygamist regimen, and to rightly question many of the tenets thereof, but without undermining the effort with undue derision and finger-pointing. His is not a hateful, one-dimensional screed, but instead an insightful, fair sketch of the pains and joys of the polygamist life (and, ultimately, our modern lives). Udall thankfully employs a more graceful approach (though never failing to expose some of the ridiculous underpinnings and irrationalia on which the faith and lifestyle is based).

We were drawn in to the book because of its potential to explore many of the concerns of our current times and relationships with spouses and children, only amplified by the polygamist setting. In this, in particular, Udall has delivered in spades. At times we were concerned that the book would devolve into a Hiaasen-esque series of environmental/development-related pratfalls, but instead Udall uses Golden Richards’ polygamist predicament to illumine how we can possibly increase our storerooms of love and be more present in a life that demands more and more of each of us, each day. While we were somewhat repulsed initially by the subject matter, ultimately Udall deftly maneuvers us to see the capacities we hold, even in the most challenging of circumstances.

This is a great read and very well written (Udall is at his best as a wordsmith in the italicized sections of the book).

Highly recommended.

Jul

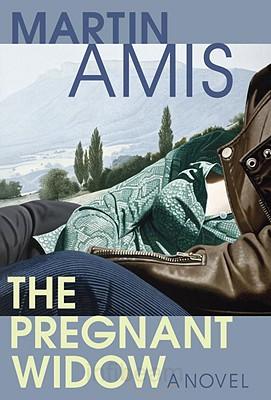

The Pregnant Widow by Martin Amis

by Lefort in Books

Having just finished Martin Amis’s most recent book, “The Pregnant Widow,” we will add this book to a small list that we recommend you read, but only if you have an unflappable, omni-euphoric disposition. We are not so disposed and are reeling around the fountain after finishing this fable. Amis is, however, one of our favorite wordsmiths still extant so it pains us to have to append this warning. Which leads to the definitive Amis gambit: if, despite our warning, you pick up this book, and if you appreciate stellar prose, you will find yourself sucked in, laughing hysterically, admiring the pregnant prose, and unable to stop even though the subject matter is, ultimately, oppressively disheartening. Side note: other books falling into this stellar-but-painful category are Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Never Go Away” (this book is inexplicably being made into a movie featuring Keira Knightley to be released in December–just says “Christmas” doesn’t it?), Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road,” and Richard Yates’ “Revolutionary Road.”

The main events of “The Pregnant Widow” are set in the summer of 1970 at a castle above an Italian village in the Campania region. Amis’s narrator looks back on that time in the castle from a 21st century vantage and ruminates on the characters’ lives and society’s evolution or devolution. College students from England have come to stay in the castle: the protagonist/narrator, Keith; his girlfriend, Lily; a captivating blonde with the suggestive name, Scheherazade, as a collection of couples and acquaintances come and go, all runwaying throughout the pages and flaunting the appetites of their youth and the era. Despite the vitality of this time and these characters, towards the end of the book we discover that Keith’s life has been largely a professional and personal disappointment, and that he pinpoints that summer in Italy as the time when the wheels started falling off.

To this end, the title of the book is borrowed from the Russian writer, Alexander Herzen, and refers to an old order about to be upstaged by a new one: “The departing world leaves behind it not an heir but a pregnant widow,” Herzen wrote, “a long night of chaos and desolation” in which the old is gone and the new has not yet been born.

Regardless, Amis is one of the most unique, intelligent writers to come along in the last 30+ years, with his cunning linguistics, hilarities, etymologies, italicisms, and unique metaphors, all of which are paraded in “The Pregnant Widow.”

Interestingly, Amis has said elsewhere that the novel is “blindingly autobiographical” and, you can’t help but believe him. We can’t help thinking of Martin’s father’s (Kingsley Amis’s) taunting observation: “Aren’t they nice, the young? They have stayed up for two years drinking instant coffee together, and now they are opinionated – they have opinions….” Correspondingly, Martin remarks on the young and their nostalgia: “Nostalgia, from Gk nostos ‘return home’ + algos ‘pain’ ‘the return-home-pain of twenty years old’.” So take that, father. We remember our nostalgia and feel it in our own.

We’ll leave it to you decide whether or not to read the book. And with that we give you below some dips into Amis’s writing from the book. You can then decide whether to dive deeper with the Widow or be satisfied with the sampling and instead sun in the shallow end.

“And the storms…were timed for his insomnias [a subject near to our hearts]. He was making friends with the hours he barely knew, the one called Three, the one called Four. They racked him, these storms, but he was left with a cleaner morning. Then the days began again to thicken, building to another war in heaven.”

“Keith lay in his bed, trying to understand [the Cold War]. What was the outcome of the dream war and all that silent combat? Everything could vanish, at any moment. This disseminated an unconscious but pervasive mortal fear. And mortal fear might make you want to have sexual intercourse; but it couldn’t make you want to love. Why love anyone, when everything could vanish? So maybe it was love that took the wound, in the Passchendaele of mad dreams.”

“And we [the Baby Boomer generation] will be hated too. Governance, for at least a generation, Keith read, will be a matter of transferring wealth from the young to the old. And they won’t like that, the young. They won’t like the silver tsunami, with the old hogging the social services and stinking up the clinics and the hospitals, like an inundation of monstrous immigrants. There will be age wars, and chronological cleansing….”

And though we disagree, this musing on the dangers of smoking set against the sarcastically characterized pains of a life long-lived (that “cool bit”) caught our attention:

“He thought, Yeah. Yeah, non-smokers live seven years longer. Which seven will be subtracted by the god called Time? It won’t be that convulsive, heart-bursting spell between twenty-eight and thirty-five. No. It’ll be that really cool bit between eighty-six and ninety-three.”

“He left her there beneath the slow, creaking loop of the overhead fan. And we don’t quite trust the overhead fan, do we. Because it always seems to be unscrewing itself.”

Martin Amis reading an excerpt from “The Pregnant Widow”: